Luma Kennedy, NCEJN Communications Manager

Last year on a warm December day, a chef, a farmer, an anthropologist and I took a walk on hallowed ground. Chef Wayne took Ms. Afraka Yates, Dr. Valerie Johnson, and me on a 4 hour exploration of a space that holds so much meaning and memories for so many in our network – The Franklinton Center at Bricks (FCAB). For those who are new here, this space is where we have traditionally held our summit since 1998.

This is hallowed ground because of its historical and emotional significance for the black community across the eastern seaboard from New York to Florida and beyond. This is a place of convergence as it sits at the crossroads of three counties: Nash, Edgecombe and Halifax. The heavy energy of this space can not be ignored.

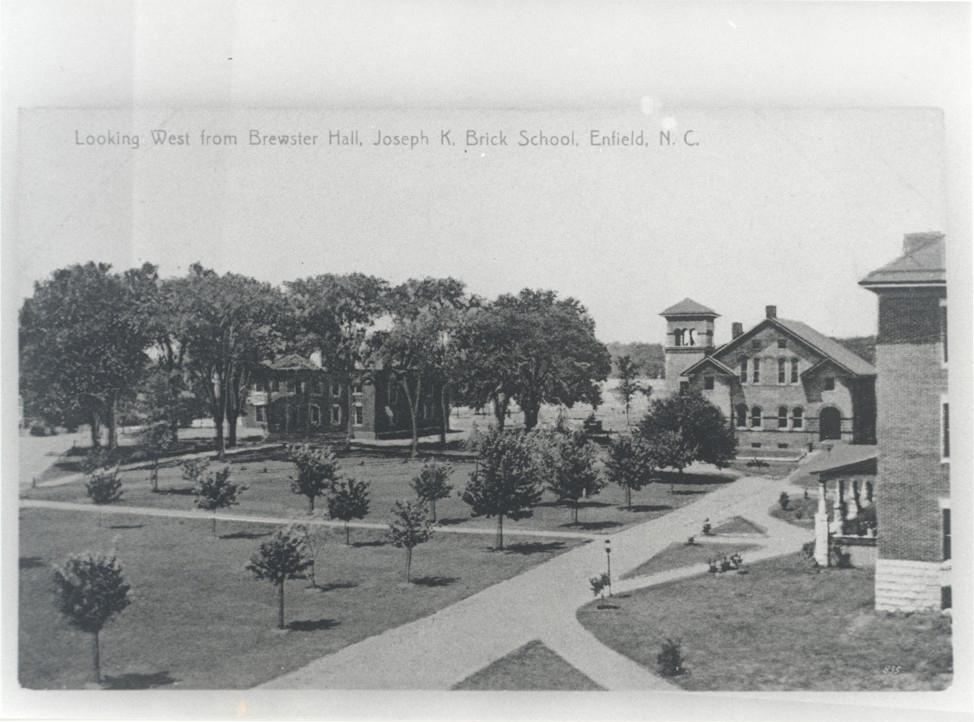

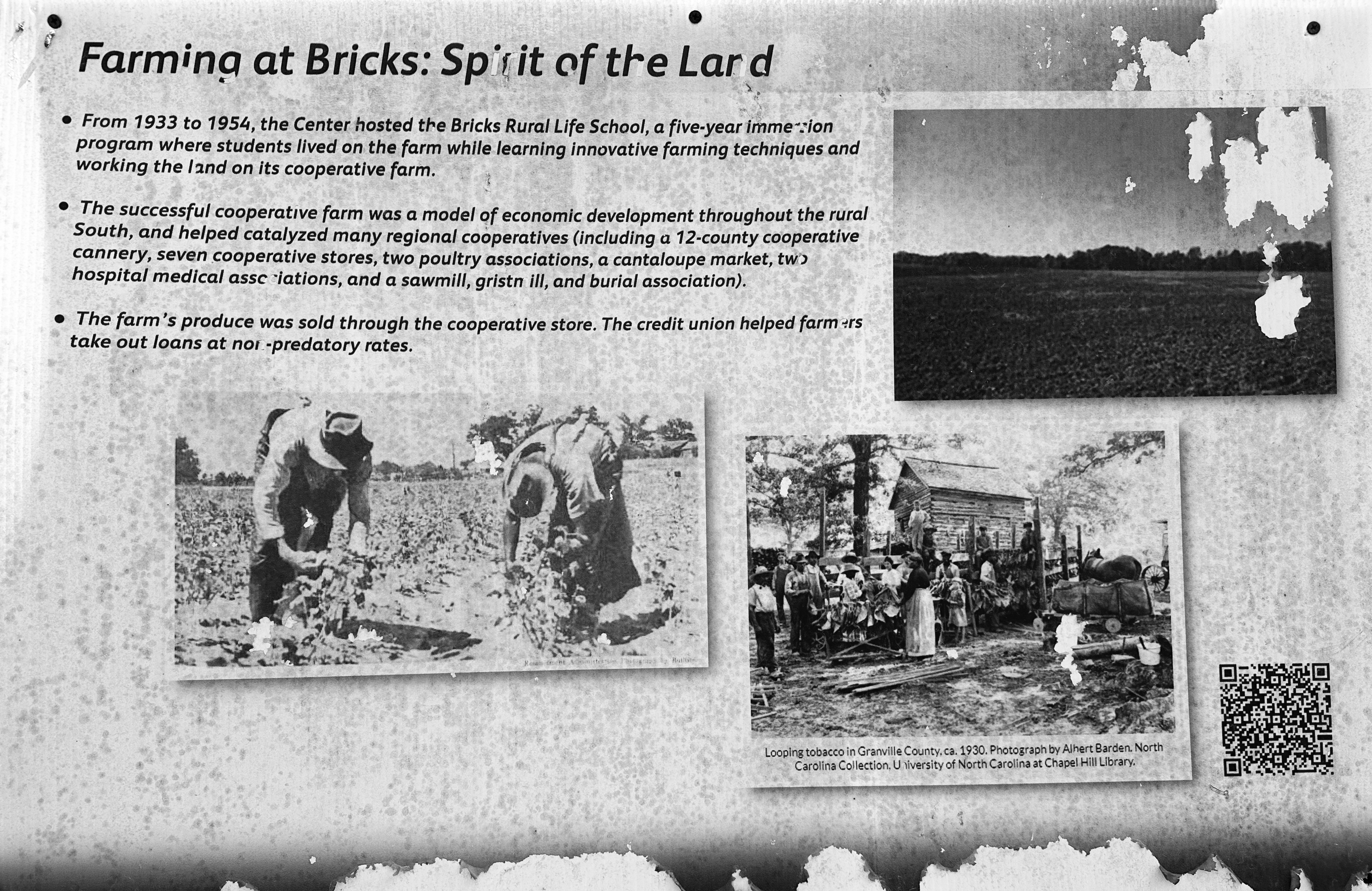

In spite of its history as a plantation (Wiggins land and later the Estes plantation), and much like its great hardwoods lining its dual driveways, in 1895 this space emerged as a place of nourishment and empowerment. In a 1937 publication written by the founder and principal of the Bricks School, Mr. Thomas Inborden shares an impressive list of assets, then later paints a picture of a regenerative agriculture cooperative that for almost forty years was an anchor, a guiding light, and a life-line for the surrounding community.

For more historic images please visit here, and for more on the history visit here.

Over the years, the design and function of the site went through different iterations: an Agricultural, Industrial, and Normal School, then a Junior College, and then finally a Rural Life School and Cooperative. Some of the historic buildings are still standing but are in bad shape, other buildings like the chapel were lost. The trees persisted (and will be getting some much needed care soon!).

Beyond the stunning hardwoods between the Inborden house and the school house, Chef Wayne led us to an old orchard with pear, peach, apple, and fig trees— still producing even though no one has cared for them in years. The conversation got spirited as we filled our pockets with nuts from the ground: the bounty of three old pecan trees at the edge of a meditative garden. This garden used to have a selection of culinary and medicinal herbs but what remains today are markers —the white tips of stones poking through the ground in a circle, with a bird bath at its center.

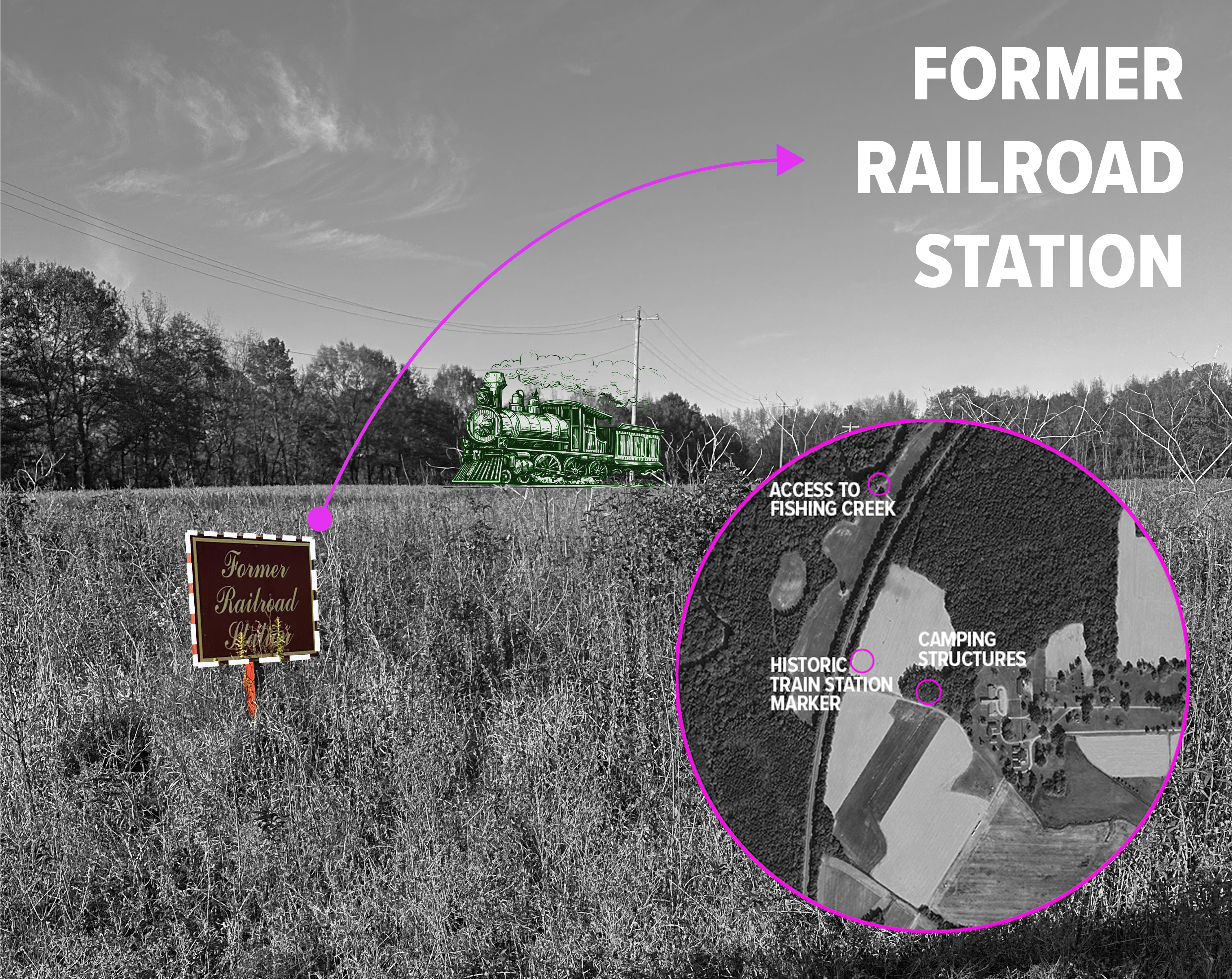

We hopped into the van and continued on past abandoned wells, and forgotten swales meant to protect the property from flooding, and finally through western parts of the remaining agricultural acres. As we passed the first forested area, we wandered in to two structures that were used in the 80’s and 90’s to shelter public school camping groups. So much possibility . . . with such strong bones these structures can be refurbished in no time!

Before we crossed over the train tracks we saw a sign marking the site of a historic train station that served the school and the surrounding community. In a place of such verdant imagination and innovation, I found myself daydreaming of the hustle and bustle of a train station. I could almost hear it!

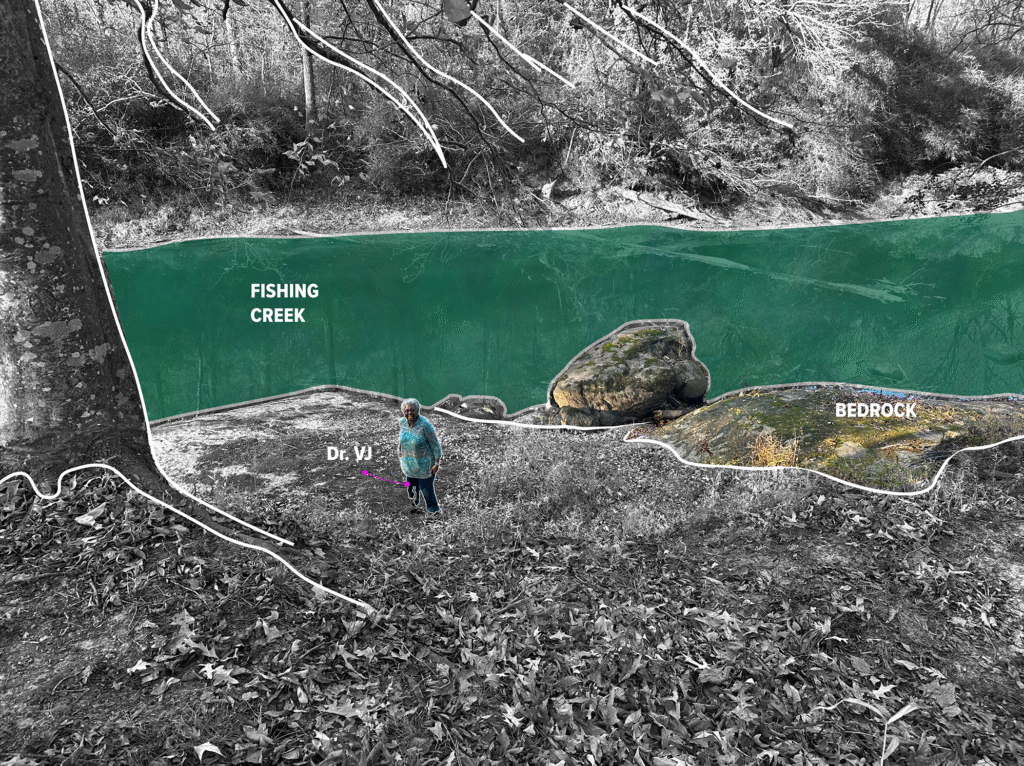

Our anticipation for our last stop was high. Uncharacteristic of a creek, Fishing Creek is wide and mighty with deep elbows and gorgeous mossy bedrock on its banks. And then there was profound stillness, and Dr. VJ, Ms. Afraka, and I walked down to the water and breathed in!

“Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.” – El Hajj Malik El Shabazz| Malcolm X from “Message to the Grass Roots” in November 1963. i.e. True self-determination requires economic and political control of one’s physical space.

Mr. Inborden noted that not a single black person owned land in a five mile radius, but by the time the school closed its doors during the depression, black people owned every single piece of land adjacent to the school. This land is not just a sum of all these legacies and all these amenities it provides. At 240 acres, it’s not just a space for social and environmental justice organizations to congregate. It doesn’t just provide the surrounding community much needed access to green space. This fertile hallowed ground is innovative defiance and resistance against decades of systemic discrimination and dispossession.*

In 2020, in tune with its history, FCAB secured funding and established an educational community garden. As you can imagine, the impact of this initiative on the community was remarkable.

This year, NCEJN and Women of Color Farmers Network (WOCFN) will be working with the Franklinton Center to secure funding and restart the community garden program. And this crew that took a journey through history on a warm December day has so many ideas and projects in store.

We will keep you posted!

* In 1895 the property was 1,129.5 acres of land.